Sitting in the backseat of the teal petit taxi, I suddenly felt hesitant and uncertain about what I was getting myself into. I’d heard many things about orphanages—they’re dirty, the children aren’t well cared for, there are too many kids crowded in one space. The list goes on. Orphanages in America aren’t very common these days, with more and more kids going straight into foster families, which are considered more beneficial to the child. Orphanages in other countries aren’t highly praised for anything, and I remember being in a psychology class in my senior year of high school learning about the mental illnesses the children in Romanian orphanages suffer from.

Each bump in the road was starting to turn my stomach into little knots. What am I getting myself into? We turn left, we turn right, we avoid potholes and pedestrians, and we come to a stop in front of a huge iron gate.

“Hopital Kortobi” the driver says smiling.

Before coming to Tangier, I knew I wanted to volunteer at the local orphanage. I felt it would be a good opportunity to realize how fortunate I am, and how grateful I should be for everything I’ve been given in my brief spell on this planet. I figured the experience would be humbling, and I would learn a lot about the culture I’d be living in for the next four months.

My entire life, I had it pretty well, despite the typical ups and downs of adolescence. Mom worked hard, giving us everything she could, and Dad lived with my grandma about 15 minutes from us. I had two siblings, a four-bedroom house in a decent neighborhood, a good education despite my constant complaints about it, and overall, I was always surrounded and supported by a loving family. I began wondering about what it must be like for orphans growing up with no family to love them.

After paying the driver, exiting the taxi, and approaching the front gate, my anxieties mounted. There was nothing to indicate to anybody that I was outside, so I foolishly tried knocking on the gate with my knuckles. Rapping on the iron bars hurt my hand and increased my frustration. I looked around for anything, a buzzer, a knocker, another person. Nothing. Finally, I heard the faint sound of a man’s voice getting closer, so I called out to him “Smah Li, can someone please let me in?”

Keys jingled, and the footsteps got louder. An older man dressed in a blue uniform said “Salaamu Alaikum” through a smile, as he opened the gate for me. “Wa alaikum salaam, shukran bezaf,” I said as I stepped over the threshold.

I wasn’t sure if volunteering at the orphanage would become a routine for me or if I would even like it. What was I doing? I had very limited experience in childcare or caretaking in general. I’d only ever babysat for family and friends, and the only jobs I had involved cooking. I was worried about the language barrier and the lack of communication I would have with people in charge. I wasn’t sure how I was even going to be able to understand what was expected from me. I didn’t even know if the kids would like me enough for me to want to visit again. Maybe they’d hate me.

I walked toward the orphanage, and, in the distance, I could see a foggy picture of a blue sky positioned above an even bluer ocean. There was a beautiful little garden with red hibiscus flowers and shiny dark green leaves on the trees. A tabby cat with green eyes and white paws groomed itself under its shade. I could hear the laughter of children coming through open windows and a woman shouting something in a language I didn’t speak.

I walked calmly on the brown tiled path leading up to the front door, and the knots in my stomach began to unravel. I started to relax.

Once I made it to the doorstep, I found a small white circle on the side of the door and pressed it. It made a screeching noise like a fire alarm, and I cringed at the thought of it scaring the children. About two minutes later, a thin older woman with a messy blonde ponytail appeared at the door. The look on her face, along with her body language, told me that she had been in the middle of something important when I interrupted. She raised her eyebrows and pursed her lips, still blocking the doorway, asking me what I needed without actually speaking the words.

I explained in English that I was a volunteer from the University of New England. A smile spread across her face when she heard “University of New England,” and she waved for me to follow her.

When I was younger, I had a huge German family that got together as often as possible for family reunions. Sometimes it took a few years to plan them because we needed to make sure every member of the family could attend. The older cousins played with the younger cousins while the adults talked about each other’s health, work, and the successes of their children. Family reunions lasted a week or more, and we all stayed tight within the group. We woke up, ate breakfast, and played all day until dinner. We’d do this every day, with never a care in the world. That’s because our parents had it all under control. We knew we would have toys to play with, food to eat, and a place to sleep at night. We were safe, stable, and content.

Soon after I entered the orphanage, I saw little children running between rooms. One had a toy in his hands, and another swung shoes by the laces. They looked at me and smiled as they ran about, and I could tell that these weren’t the neglected orphans I’d learned about in high school. These kids had round, full bellies, clean faces, and bright happy eyes.

The woman turned back to me and said “Babies?” pointing to the staircase in the right corner of the room. I nodded, and she continued walking toward the staircase. A tall potted plant sat in the corner of the first landing, its glossy green leaves reflecting light from the sun peeking through the window.

At the top of the stairs was a white wooden baby gate that the woman unlocked for me, and we passed through. I closed the gate and shut the little metal latch, and I was introduced to another woman in traditional Moroccan garb. This woman, thankfully, spoke English. She explained that the mission of the orphanage was to provide “Tender Loving Care” to all of the children and make sure they were fed, changed, and played with every day.

After I talked to the woman about the orphanage, she asked if I would help feed the infants. I sat down on a wooden chair at a large table next to four other women speaking French. One by one, someone brought me infant after infant, and bottle after bottle. Cradling each baby in the crook of my arm, I admired their long black eyelashes and button noses. When feeding and burping the babies was done, I was brought to the toddler room. This room had a large mat it in the middle of the room, a white table full of stuffed animals underneath a TV airing an Islamic children’s show, two rocking horses, a swinging chair, and ten children under the age of two in their cribs.

I walked around the cribs saying “Salaam” to each child before lifting them from their cribs and putting them down on the mat in the middle of the floor. “I don’t want to come in here and see any child still in their crib; they all should be out playing,” said the English-speaking woman to me. There was another volunteer about my age, so my responsibilities were divided. I was able to focus on a few children at a time, instead of ten at once.

Once the English-speaker left the room and we were alone with all of the children, I felt overwhelmed. How was I going to handle looking after so many kids at once? Even though there were two of us in the room, it felt like I was constantly moving the children around, so they weren’t stuck between cribs, chewing on splinters of wood, pulling another kid’s hair, trying to escape the room, or falling off the mat onto the tiled floor.

Then, just as I picked up two kids, one in each arm, and placed them back onto the mat to play, I noticed a little girl smiling at me with a scrunched up nose and eight little white teeth. I went over to her and handed her an orange ball, and she giggled. Her eyes, skin, and thick curly hair were different shades of brown, and she was wearing a gray sweater with a pink bow on it and dark jeans. Her name was Swaila.

Growing up in Pittsburgh gave me a good balance of city and country – the perfect playground for a kid. I could play in the yard, chasing butterflies and catching snakes, or I could jump over cracks in the sidewalk and splash in the water runoff by the curb after it rained. My little sister was my favorite playmate. Together we liked to blow bubbles under our swing set; make soup out of mud, twigs, and berries; play teacher with my old school workbooks; sell flowers and painted rocks on the side of the road; and celebrate every holiday and survive every family gathering. I always had a friend by my side to face life with, and we both taught each other invaluable lessons growing up. I never felt alone.

At the orphanage, I spent the next hour and a half chasing after children, fixing loose socks and tickling laughing babies. When it was finally time to leave, I caught myself thinking about how the entire time we were in the toddler room, no one came in to check on us or the children. How much attention would the kids have gotten if we weren’t here playing with them? I thought about Swaila and what kind of life she would have one day. I wondered if she would ever be adopted. Would she ever go to school? She didn’t have siblings in the orphanage with her; but the other children were her playmates and I guessed in a way, they were her family.

The other children were also her competition when it came to finding a home. I wondered if Swaila would be overlooked because of her personality, looks, age, and background? She was already a year old, and statistics say that the older a child is, the less likely they are to be adopted. I wondered if she felt lonely when it came time to leave, and we put all of the babies back in their cribs. They were all sitting or lying in their cribs, and Swaila and a few others had tears streaming down their faces as they reached up to us pumping their little hands like a cat stretching its claws. My heart sank at the sound of them sobbing as we closed the door behind us.

When I was younger, I used to get belly aches every holiday. I didn’t know how to control my sweet tooth and ate so many of my grandma’s cookies at Christmas until I would throw up later. I’d sit on the floor of my bathroom as my mom rubbed my back. She’d ask me calmly how much junk I’d eaten. She’d name the list of foods I’d eaten throughout the day, and I’d feel sicker as I recalled everything that was sitting in my belly. Eventually, though, she’d shush me as I cried, and the more she rubbed my back and ran her fingers through my hair, the better I would feel. No Pepto Bismol or Tums ever cured my belly aches quite like the soothing touch from my magical mother.

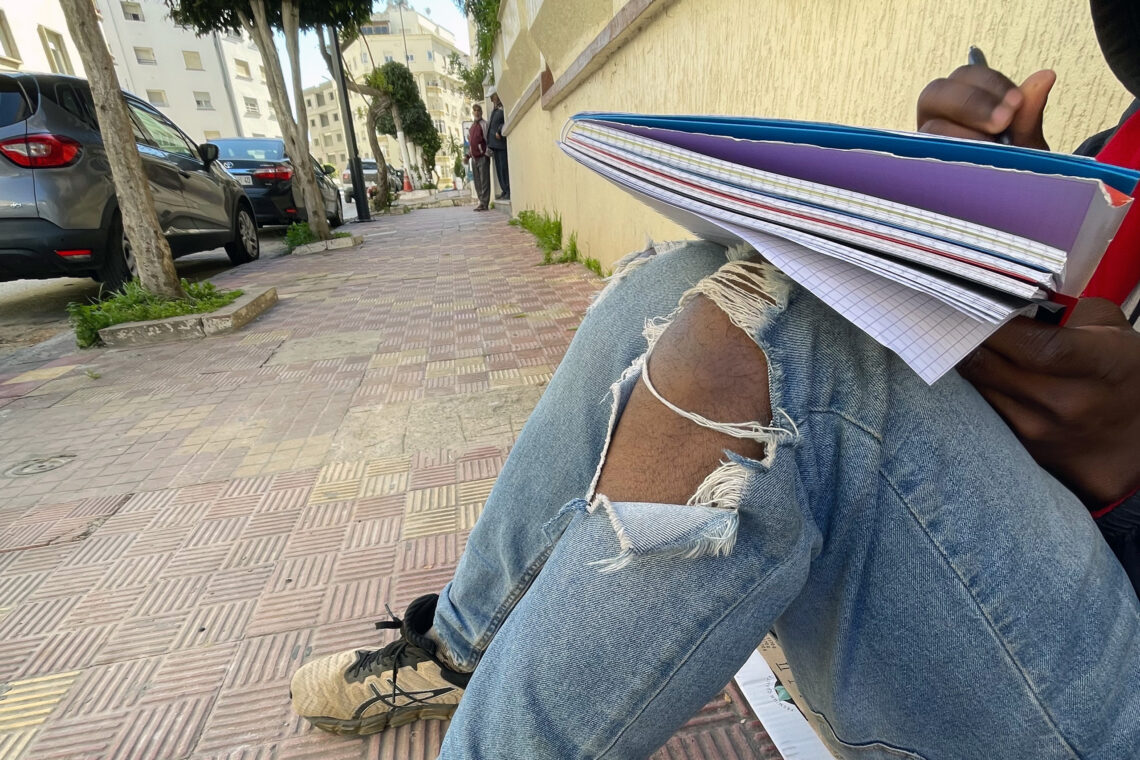

I exited the same way I came in, through the front door and the iron gate. Sitting silently in the backseat of another teal taxi, I reflected on the events of the day and on my childhood memories.

I thought about Swaila again, and it seemed like everything she did reminded me of different aspects of my childhood. When I tickled her and she laughed, I thought about my older cousins tickling me and laughing until I couldn’t breathe. When her nose was running and she stumbled around the room with toys in her hands, I thought about all the times my mom cared for me when I was sick. It was strange that a child in another country with a completely different background could remind me so much of home and my childhood.

Regardless, I had to leave the orphanage and Swaila behind. And eventually, I will have to leave my new home in Tangier to go back to my home in America. I came to realize that there were many things that I loved and hated. I suppose it’s the same when I’m living in America. In Morocco, I love that there is a place for children to go when their parents don’t or can’t care for them. But I also hate the fact that there are rooms full of kids that can’t find perfectly capable parents in a loving home because the adoptive parents aren’t Muslim. I agree with the Muslim religion and the practice of kindness, peace, charity, and loyalty. But I don’t like that if you break a taboo, such as having a child out of wedlock, all those values get tossed to the side. And the only charity left is donating another child to an already crowded orphanage.

Back on campus, I had a much greater appreciation for the things I take for granted every day. I realize how strong my mom, a single divorced parent, was in raising us. As I said, I was thankful that I was given the opportunity to work with the orphans in Tangier and I had a new respect for the workers at the orphanage for providing these abandoned children with the best they can give them, given the circumstances. I still don’t agree with the adoption process in Morocco and I don’t know if Swaila or the other children in the orphanage will ever find homes or receive the kind of education I took for granted, but I do know that while they are in the orphanage, they will be given the best that the caretakers have to offer.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.