You can feel it in the air, in the way the birds chirp, the way people bustle about. The children laugh on Friday, their Holy Day, and there is no stress. The air takes on a peaceful, welcoming scent, like cookies and coffee on Sunday in a Baptist church. Here in Morocco, it’s the fresh scent of turmeric couscous and steamed veggies as you walk through the Medina, holiness emanating off the ancient walls like desert heat. Settling in the dust that lines the streets and driveways of Tangier. Like snow that settles the winter stress in Alaska.

When I was a child in Anchorage, Sundays were anything but peaceful. My family would wake up at 6 am to be at the building by 7:30 am, eating sausage egg McMuffins from McDonalds on the way. The entirety of the church was contained to two to three white trailers, what we called a portable church, pulled by my dad and the worship leader, a short man from Ketchikan with a long red beard. I would help unload the trailers, in gloves and winter coats to protect us from the unforgiving Alaskan winters. I would help set up the children’s area, and my mom would make sure everything went according to plan; she practically ran the place herself. The trailers would be finished reloading around 2 pm, and we would go to a local restaurant on my parents’ limited budget, the pastor paid himself and his unemployed wife more than my mom would ever make working for them. I spent my summers eating cheap Costco hamburgers and snow cones and cotton candy, as we forced religion upon the homeless people of Anchorage and the families living in trailer parks. Thinking they’d somehow be better off if they just had Jesus.

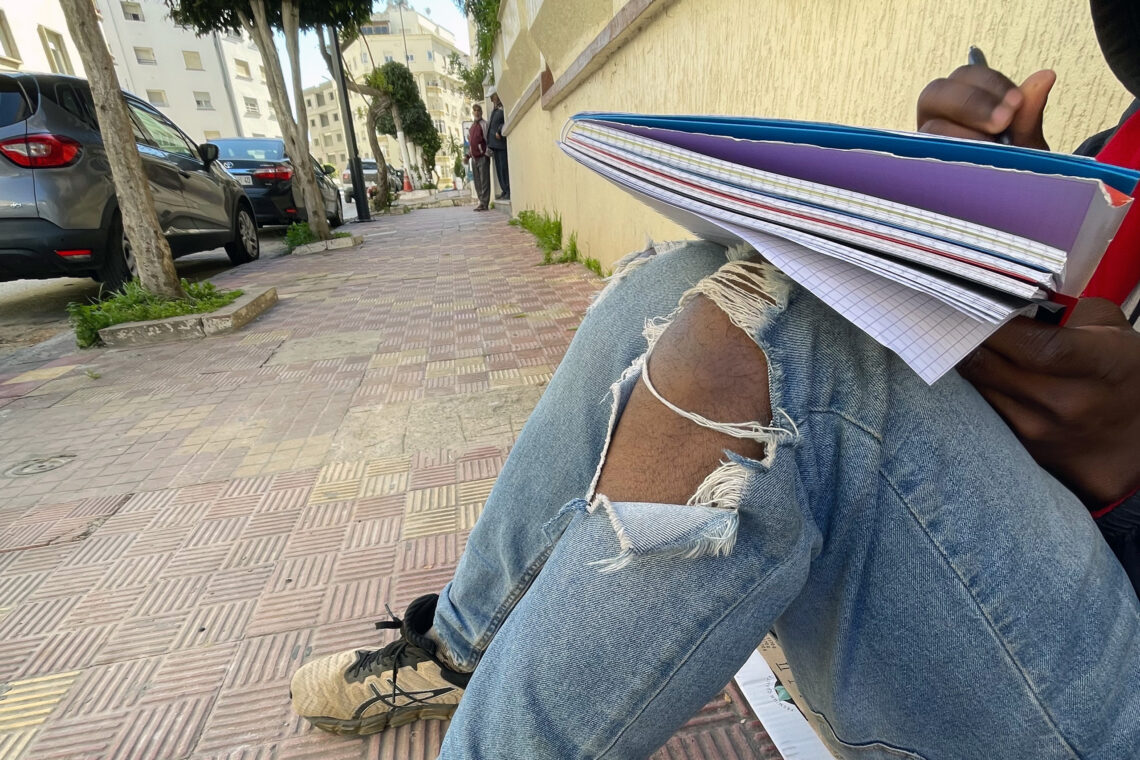

As a sophomore in college, I chose to study abroad in Tangier, Morocco. I never thought I’d step foot in Africa, or a Muslim country. I didn’t know what to expect or what to feel when I arrived in Tangier. The palm trees surprised me but made sense when I thought about it. I was scared of earthquakes even though I knew one probably wouldn’t shake. I knew nothing about Islam. I was a blank slate.

I stood on the ledge of the two-person dorm room holding onto the ornate blue iron railing, overlooking the red and beige walled layered neighborhoods of Tangier, the Mohammed V Mosque peaking out above, tallest in Tangier. Taking it all in. The ocean breeze off the Atlantic and Mediterranean, rejuvenating and fresh, frizzing hair and cooling skin under the warm African sun. The prayer call goes off from the mosques, cornering me. I thought it was an alarm, some sort of emergency, like a tornado warning, but then I heard the singing.

It stirred me, ruffling the feathers of my soul. The more I heard it, the more it affected me and disturbed something deep inside me. Each time it played, blaring from the mosque up the street, something in the dark recesses of my soul churned, religious food poisoning. The more I learned the more this web of knots inside of me twisted. It all came loose one evening. The prayer call pulled the right strings in my knots of prejudices, undoing them so I could see clearly. Unraveling dark parts of myself I thought I’d left. Like pulling at a thread in a pashmina scarf, they all fell apart. Religious biases and prejudices I thought I’d let go of, left behind when I left the church. Revelations about religion.

I threw it all up, nasty with religious bile. How wrong the Christians are, the Americans are, against Africa and Muslims. “Love everyone,” but not those whose religion is different from yours, whose skin color is different and whose culture is different. I think they’d be surprised how similar Christianity, Catholicism, and Islam are. I think it would shock them to their core, just as it has me.

New memories resurface on Fridays in Tangier. No one is stressed, they work in the morning and pray in the afternoon, and their Holy Day is peaceful. Prayer and sermons are played from the mosque, and the atmosphere of the city changes. It’s subtle, but you feel it, in the air and the people. Charged with holy electricity.

I don’t know the words to the prayer call, I don’t know what the muezzin says or if he sings it live, or if it’s just a recording. I’ve been told the lyrics. How each verse is said twice. But I don’t remember what is said. Sometimes it sounds different, even though I know it’s the same. Sometimes I think it goes off at different times of the day, even though it’s supposed to go off at almost the same time. I know it’s different on Friday, the lyrics change and it’s more distorted and melodic and in a way it scares me. The way the air feels after, it’s like I have somewhere to be, something to do. The birds become busier, screeching at each other. Like everyone in this city knows there’s something to be done: pray.

I don’t pray, but the palm fronds flap in the wind around me, like they’re waving at me, signaling me that I should pray to someone for the sake of my sanity. But the prayer call is an integral part of my day in Tangier, prayer is integral to the people of Morocco. Whether I hear it during physics, in the evening from my room watching the sunset, from the academic building, or in the Medina. You can hear it rev up sometimes, slowly and quietly and you almost mistake it for a loud motorcycle until it gets louder and louder and then the singing begins. Slow at first, letting the first verse reverberate across the city, reaching every cat in every corner, racing across the flat rooftops of Tangier. He repeats it, then moves to the next verse, singing them closer together. And then it fizzles out, and the air and the birds return to how they were before it rang.

Sometimes I don’t hear it, and my day feels like a peaceful illusion, a pleasant trip on reality. I couldn’t hear the prayer call in Rabat. Not once. I never heard it rumble through the streets, interrupting my afternoon reading of Dune. Never heard it while we were out in the city. I didn’t hear it at all. It was strange and peaceful. A song that rings every day and I use as a timestamp, marking the hours. But it didn’t sing, not in Rabat. But it was undisturbed, this eerie and loud melody not filling my ears five times a day. I didn’t hear it the evening we arrived there, after eating true Moroccan cuisine. Large tagine dishes smoked with flavors, one was sweet with beef and dates and another was lemony with olives and chicken and french fries and the other was egg noodles and chicken seasoned neon yellow from the turmeric. Mint tea the workers poured from the ceiling, and we left before it got busy.

I didn’t hear it when we were in the gardens, Andalusian style with cats strolling through rose bushes and beside sour orange trees. I didn’t hear it in the Medina, the small portion we explored. Why wouldn’t I hear it in the Medina, the most ancient and religious part of the city? Why wouldn’t it call out, ringing throughout the streets and over the enormous sprawling cemetery next to us? I couldn’t hear it in Rabat, but surely it went off. Surely it was played from the speakers of the mosque in the capital city. Maybe I was too far away, or maybe it wasn’t actually played, but I doubt that.

I didn’t hear it in Marrakesh either. With its stucco walls from red clay and palaces made of the most ornate mosaics and carved wood and stained glass. Maybe it can’t be heard over the rain, flooding the mountains and dampening the mud walls of the city. Maybe I wasn’t close enough to the mosque but I could see the speakers through the restoration on the top part of the tower. Maybe I couldn’t hear it over the noises of the Medina, men trying to sell me sunglasses and fruit juice and motorcycles racing through the narrow streets. I didn’t hear it at all. I thought maybe it would sound different in Marrakesh, echoing off plaster houses compared to the more modern walls of Tangier. But I never heard it, and I don’t know why.

At night, the Mohammed V mosque glows with green lights, like a Muslim lighthouse, standing regal above the layered city of Tangier. And I have the perfect view out my window. The crescent moon made brighter by the African night, short wisps of midnight clouds glaze over the mosque. I don’t know why it’s such a monumental part of my life in Tangier. I don’t want anything to do with any religion. And yet, it greeted me the first night I was here, unraveling deep dark parts of myself I didn’t know still existed. I was shaken to my core, to the deep recesses of myself.

But I think I’ll miss it when I have to go back to the States. The only sound will be street traffic and Fridays will be normal with science and sociology classes and no couscous, and the days will pass quietly, uninterrupted.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.