I felt my forehead wrinkle up in worry. My interview was supposed to be in five minutes, and I was still on campus. Just as I was convinced that Mourad, the campus manager, was not going to show up, he rushed into the room, panting like a marathoner running crossing the finish line. Wearing a white soccer jersey and charcoal grey dress pants, the thin man looked frazzled. “Come! Come! Let’s go.”

In our mad dash to get to Dar Tiqa on time, Mourad ordered one of the kitchen workers to meet us at the gate with a bronze van. He glanced down at his watch several times and then began speaking a blend of French, Arabic, and Spanish to the kitchen worker. I stared at them blankly, dumbfounded by this babel of languages.

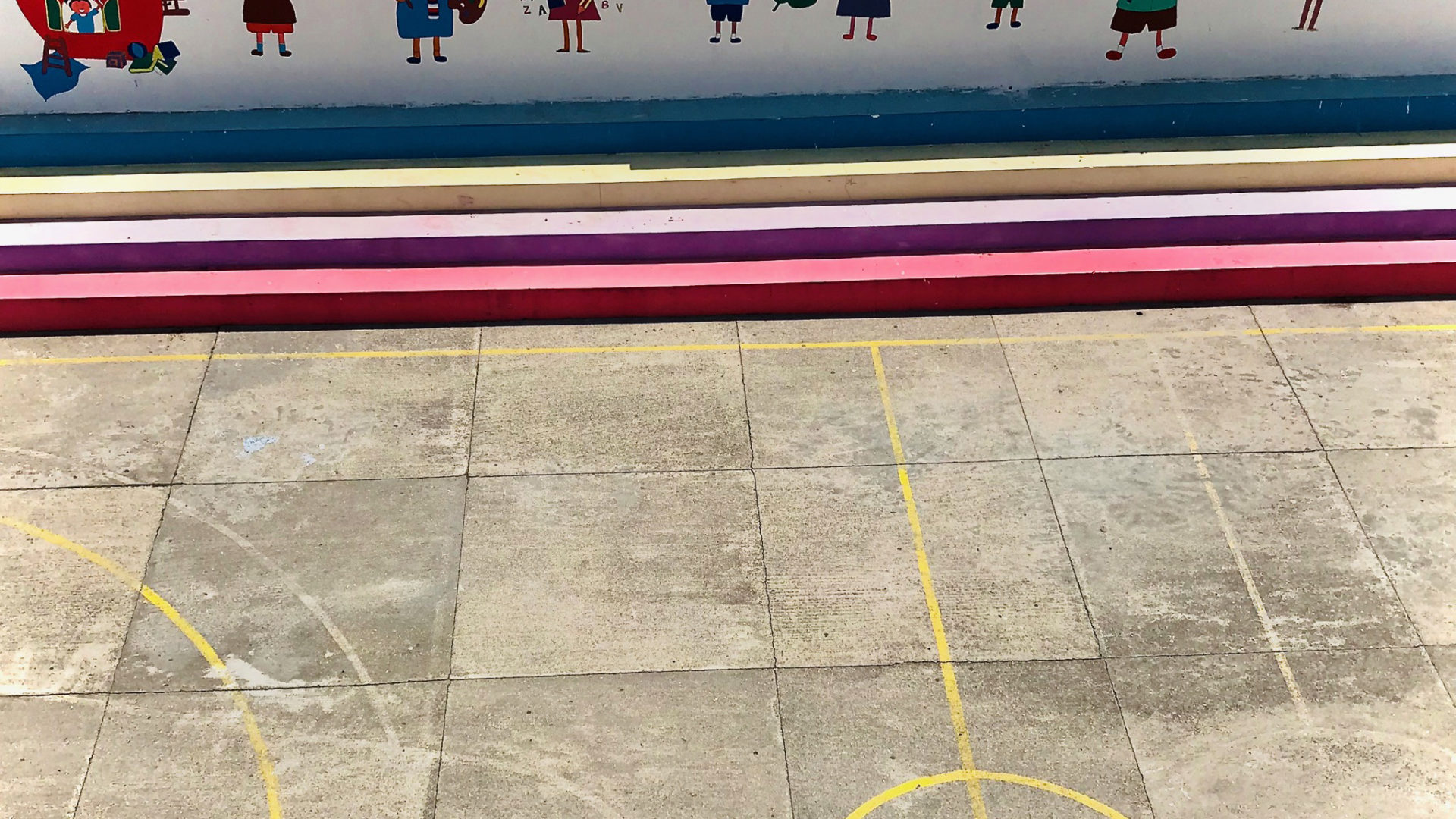

The driver dropped us off on Avenue Pasteur. With Mourad setting the pace, we continued along a back street, passing small shops and markets, and then down graffiti-covered steps. Finally, we arrived at Dar Tiqa, a foster home run by Catholic nuns. Large doors and high gates divide Dar Tiqa from the rest of Tangier.

In preparation for the interview, Mourad gave me some background information. Courts have placed the girls at Dar Tika because of physical neglect, sexual abuse, or some other tragedy. The nuns and the women who work for them strive to provide these girls with the opportunity to have a normal, healthy life. From my interview I hoped to gain an understanding of how the nuns find the motivation, day in and day out, to take care of the girls. Even more, I wanted to know how they maintain the belief that each child can overcome her difficult past and follow her dreams.

Entering a second gate, and we took a quick left into a small room where I knew one of the nuns would be waiting. The walls were blank, and in the center of the room was wooden table etched with the names of girls who have passed through Dar Tika. I wonder where these girls are now. I thought to myself. Who have they become?

Aziza wore bright blue eyeliner, a light pink shirt, and a matching sweater. She radiated the kind energy I want to be surrounded by. Her urgency to start the interview also reminded me that she is a very busy woman.

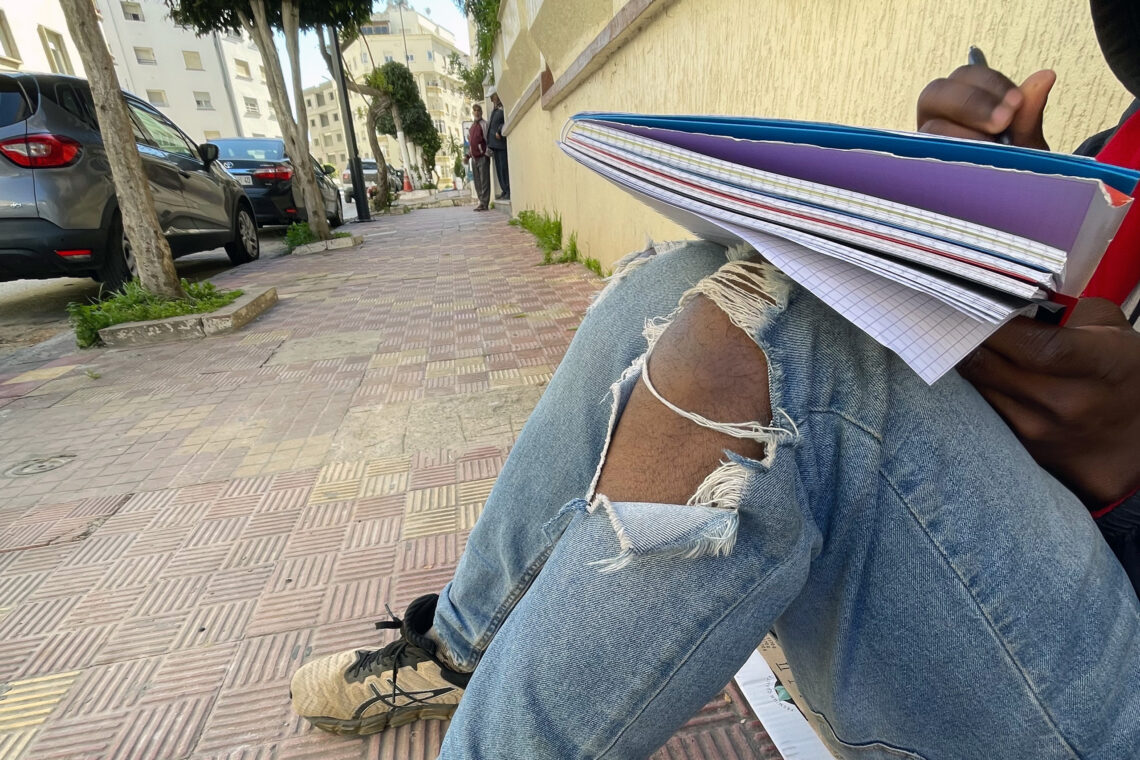

Excited to finally conduct the interview, I flipped open my magenta notebook and grabbed a cheap pen from the inside pocket of my purse. Then, with Mourad translating, I asked her my first question. “How did you end up here?”

Aziza shrugged. Mourad, chuckling, replied for Aziza:

“Sometimes things just happen, and you end up where you need to be.”

How true, I thought. So many times in my life, I’ve had no clear direction. Sometimes out of fear, I’ve made decisions based on other people. My decision to come to Morocco was my way of living a purposeful life. I knew leaving the United States would force me to be more authentic.

My follow-up question was about Aziza’s responsibilities at Dar Tiqa. She responded with a long, detailed list. Aziza was responsible for getting the girls to their schools, cooking for them, and making time to chat with each girl individually on a regular basis. Sometimes this requires being persistent in the face of the moods or struggles the girls might have. When they first arrive, many traumatized girls fail to notice that this place was created to give them a future rather than strip them of one, and they lash out.

The girls, Aziza said, do not heal “overnight.” It is a long process of growth and development, and each girl adjusts differently. I tried to imagine what it would be like to be one of the girls, thrown into a new environment with no idea what to expect. Even if I’d been hurt by them, would I miss my family? In their shoes, would I know the difference between right and wrong, good and bad, help and abuse, struggle and success?

With these questions on my mind, I continued the interview.

“What do you teach the girls at Dar Tiqa?”

According to Aziza, the most important thing she can teach the girls is “how to live an independent life.” “If the girls are given love, stability, a set schedule, and an education, they no longer are defined by their circumstances.” Her hopeful tone sent shivers down my spine.

We next spoke of the most rewarding aspects of Aziza’s job. She told me how she celebrates when the girls can go back to their families. I thought how this must restore some faith in humanity for her and the other girls who remain at Dar Tiqa. Aziza went on to tell me how amazing it is to have girls that grew up at Dar Tiqa return to visit after making a successful life of their own.

Over and over, she returned to the “smile,” each time moving her index fingers across her mouth. When the girls smile, she is happy and feels successful. It was as simple as that.

I told her that I hope one day as a nurse to have an opportunity to do similar work, then asked her how she stays motivated. “If you believe in them, they can feel it, and they will grow.” She also told me how important it is to be patient. The girls not only have to adjust to a new environment, they also have to learn to trust themselves and others.

At the end of the interview, Aziza invited me to meet the girls. Unsure of what to expect, I stood outside the open door where all the girls sat listening to music and doing crafts. I had no chance to overcome my fear of the unknown before each girl jumped out of her chair and rushed to kiss each of my cheeks. They had no fear or hesitation. It was apparent how strong-willed each and every girl was. Their ages varied but one thing was sure: they were a lot more mature than I was at their age. I couldn’t help but smile in admiration at how confident they seemed.

At that instant, I thought about Judy Pazourek, the person who inspired me to become a nurse. Judy was a distant cousin I first met when I was about ten years old. She lived in Baltimore and her house became our family vacation spot. I became close to her very quickly. She was one of those people who are so selfless and considerate of everyone else that you wonder what their secret is. Now retired, Judy spent her career working in a hospital run by nuns. As a Catholic, she accepted the good and the bad in everyone. Cousin Judy always found a way of making me see the beauty and purity in everything.

Judy’s perspective made me want to be just like her. The way she spoke about how deeply my fourteen-year-old father was affected by the loss of his dad, or about my parents’ divorce, helped me understand that life isn’t perfect, nor should it be. Without pain, we wouldn’t know how to feel joy.

Judy passed away from cancer when I was seventeen, and I never got the chance to say goodbye. I only wish that my choice to help others will make her proud. I know she would be proud of how big my world has become since I’ve arrived in Morocco.

Walking back to campus, I reflected on my brief time at Dar Tiqa. What I found there was a living, breathing version of relentless perseverance. Wow, I found myself thinking. Here you are, Keara, doubting your ability to be there for people when these eight-year-old girls refuse to give up on themselves after experiencing more trauma than you’ll probably ever have to face. If that doesn’t motivate you, I don’t know what will!

With those thoughts, I smiled the entire way home.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.