It’s early in the morning just north of Rabat, and a little boy is standing on a pile of dirt, watching the high-speed train gun through the outskirts of his village as if in one of Wes Anderson’s pastel, symmetrical landscape. However, the symmetry is off here. Just behind the boy’s pile lay hanging laundry against the backdrop of crumbling brick and stucco. The old concrete structures look almost empty. Shepherds herd their sheep in the grass, and yellow wildflowers wave in the breeze.

I sat on the train, looking through the window at the boy. Given the speed of the shiny new TGV, I saw him for maybe a second before the train whooshed behind a concrete barricade. “Poverty blockers,” I thought to myself, but quickly reconsidered. This was farmland, and perhaps engineers built the wall to prevent kids and valuable farm animals from ending up on the tracks of an unstoppable train roaring at 200 miles per hour through rural Morocco. The boy on the pile was now well behind us, but his image stuck with me.

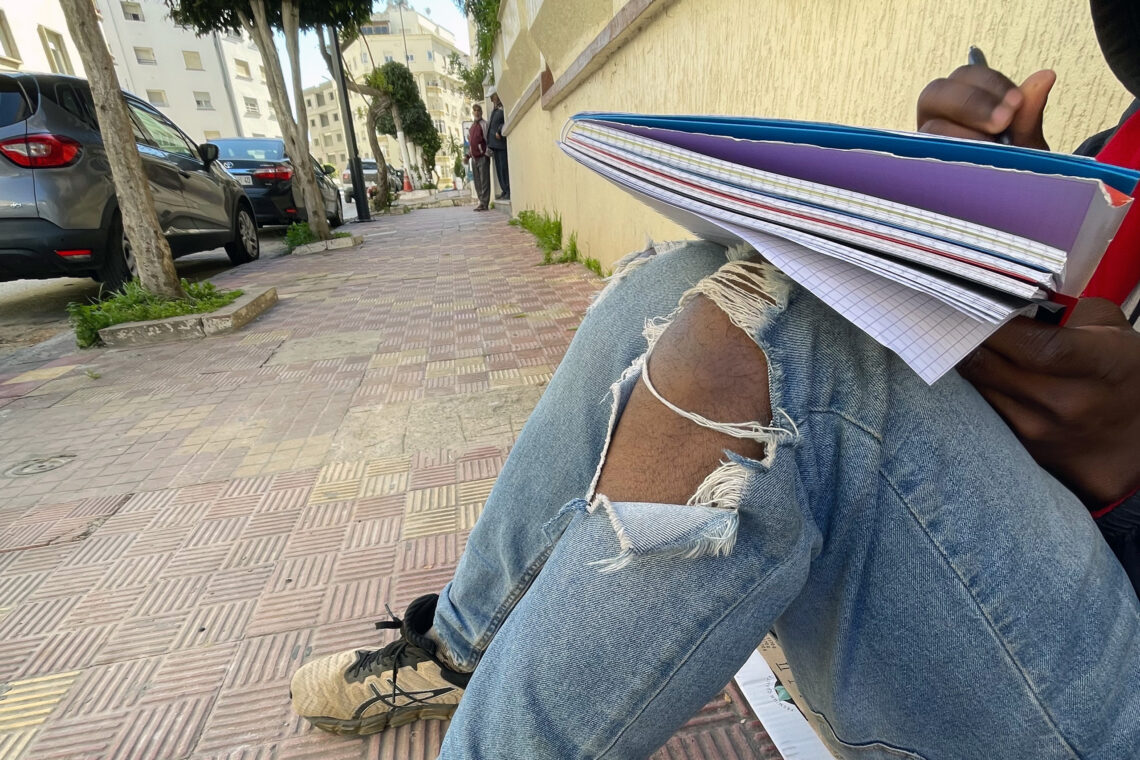

It got me thinking about gratitude — how fortunate I was not only to be in Morocco, but also to be quite well off here. It wasn’t my choice to be born in America; it’s simply my right of birth, just as the boy on the pile was born in a village and Morocco’s King Mohammed VI in a palace. The boy looked at the high-speed rail, possibly wondering how us well-off folks live and travel, just as I looked at him, wondering what it was like to have his life. He wasn’t in rags, but I assume he certainly didn’t walk around in Tangier like me, casually saying “It’s only 50 dirhams, that’s like five bucks — not a huge deal.”

A few days later I was on the same train roaring north back towards Tangier. We passed the same farmland as the sun was in the final stage of sunset on the cusp of blue hour. The boy was not on the pile, but even without him there I felt a connection. I had grown up in the rural farmland of Western Massachusetts, and perhaps the people traveling between Boston and New York passed by my working-class town and thought the same thing about me as I had about the boy.

However, I know from experience that a childhood of being around people who know how to use their hands and work long days is something that gives you an edge. That boy might not have many dirhams in his pockets; but compared to an investment banker on Wall Street, I don’t have many either. No, I’m not a millionaire or a king, just a kid from the country. A kid who used to climb on piles all the time as a boy.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.