When I first looked into the eyes of Imane, I saw a woman who is on fire. Her fierce advocacy of the natural birthing process and breastfeeding got me reflecting on how I, too, can develop the burning passion that will plaster a grin on my face and get me jumping out of bed to change the world every day.

To meet Imane, my friend Laura and I took a turquoise taxi on a sunny Wednesday morning and set off to find the skate section in the vast Perdicaris Park in Tangier. After stepping out of the car, we turned to the right, entering the wooded side of the park, walking along a gravel path flanked by trees so tall they seem to be reaching for the ominous clouds above. I felt like a Girl Scout back at camp in upstate New York, a place where I spent one weekend every year for about ten years. Laura thankfully reads French, but she didn’t see any signs for the skate park, only a sign saying sport or recreation. I begin to worry because, with no cell reception or Wi-Fi in the park, I had no way of contacting Imane to tell her we’d gotten ourselves lost.

We wandered for ten minutes before arriving at the edge of a cliff where we had a panoramic view of the Tangier coast. Trees lined the cliffs and the Mediterranean waves crashed on the shore below, their rhythm forming a calming cadence. I took a deep breath and inhaled a fresh sense of hope that we would find our destination. I thought we had arrived when I spotted a sports park equipped with wooden obstacles, similar to “American Ninja Warrior.” But there was no halfpipe or anything else specific to a park designed for skateboarding.

Deciding to change routes, we backtracked through the park and crossed the main road to the other side near the road where the taxi left us. Laura spotted a white staircase in the distance, and we set off after it, hoping our destination would be on the other side. Sure enough, after over twenty minutes of walking, we found ourselves alone in the skate park—along with a swarm of bees. I felt a pain so sharp my eyes welled up. I am deathly afraid of any bug that crawls, flies, and, especially, stings. How ironic, I thought rubbing my wound, that despite growing up in a family of avid gardeners I’d managed to avoid bee stings until now. I guess I had to come all the way to Tangier for that.

Glancing to my right, I noticed a woman wearing a black hijab and a matching black long dress, complemented by a growing smile on her face, elegantly descending the white staircase. Though I had no way of knowing it was actually Imane, I felt it was her. As I gravitated in her direction, I noticed she had several excited children following her, each one carrying a bag of roller blades, helmets, and scooters. At first, I didn’t say much beyond confirming that I was the woman who’d been swapping messages with her for the past couple of days over WhatsApp. With smiles all around, I gave Imane a couple of minutes to get her children equipped and made sure everyone had their helmets clipped and rollerblades straps tightened.

Gripping my spiral notebook and pen, I started in on basic questions once each of the four kids skated or scootered into the park. “Where are you from?” I asked. “How many kids do you have? What do you do for a living?”

I learned that Imane, her husband, and four children were born and raised in a town in Northeast France. Her family moved to Tangier from France in 2016, five years after France banned women from wearing various forms of Muslim headscarves, a policy that grew out of the effort to separate all religions from the state school system. While she didn’t say that the ban on the hijab was her only reason for leaving France, I imagine the decision played a central role. Imane and her daughters are traditional Muslims and proudly wear the hijab. Morocco, specifically Tangier, is welcoming to different religions and cultures, and was an ideal place for them to escape the stereotypes and pain that France caused their family by banning Muslim headdresses. Another reason they chose Tangier was that the city gave Imane new opportunities for work.

I knew prior to conducting the interview that Imane is an advocate of both breastfeeding and natural birth. She is a volunteer in Tangier at GNO Provinces, a clinic not too far from the UNE campus which supports and provides information for mothers who are interested in natural birth or who want to learn more about breastfeeding. This organization is international, with a US branch founded in 1956. The clinic runs classes on natural birthing every three weeks.

I’ve been interested in breastfeeding ever since I learned how it strengthens the mother-baby bond, reduces the baby’s risk of having asthma or allergies, boosts the baby’s immune system, and lowers the chances of ear infections or respiratory illnesses, so I was excited to pick Imane’s brain.

There in the skate park, Imane explained to me that “breastfeeding is very instinctive and mothers need to imitate others. It’s a natural process, but mothers need to see another mother breastfeed.” A woman may not simply pick up her baby and know what to do. If a mother can see others breastfeed, she will be able to relax and continue with the process.

The other aspect of mothering that Imane is passionate about is natural birthing. She was introduced to this idea in France. After extensive research, Imane decided that when she was pregnant with her first child, she would mother “like our ancestors.” To get “close to the ancients,” her children would also sleep with her, and she would breastfeed them until they didn’t want to. Her goal as a mother was to “respect the child’s needs.”

She and her husband decided that their first child was going to be born at home with a midwife. She didn’t tell her parents about the birth until after her daughter was born since she assumed they would be scared. She described this experience as very personal and relaxing, allowing her to experience minimal pain. Her husband even felt more a part of the process, minute by minute, than he would have been in a hospital setting.

Many women dream of giving birth, of being overwhelmed with joy and love for their new child. As Imane explained, “childbirth is a spiritual process which needs a lot of privacy.” Imane spoke highly of the well-known French obstetrician Michel Odent; she spoke highly of his books that explain how “hormones make us need privacy and that if all conditions are not met and the mother does not feel secure then her stress levels rise.” Adrenaline is a major player in the birthing hormones and is the one which has the ability to restrict other hormones during the birthing process and cause labor to prolong. Imane added that “adrenaline is even released during orgasm, which is a very important stress inhibitor.”

Curious after finding out that many midwives are used throughout Morocco, I did more research into what they do and how one becomes a midwife. As I presumed, most Moroccan midwives have a background in nursing and then complete a secondary midwifery certificate accreditation. They work in either hospital or clinics and are trained to keep the mother calm. They seem to be a popular option due to their lower cost compared to obstetricians, and they allow a mother to be in the comfort of her own home when welcoming her child into the world. Personally, it would be a hard decision for me to use a midwife instead of an obstetrician. But it is intriguing to know that there are options for nurses to specialize more in their profession.

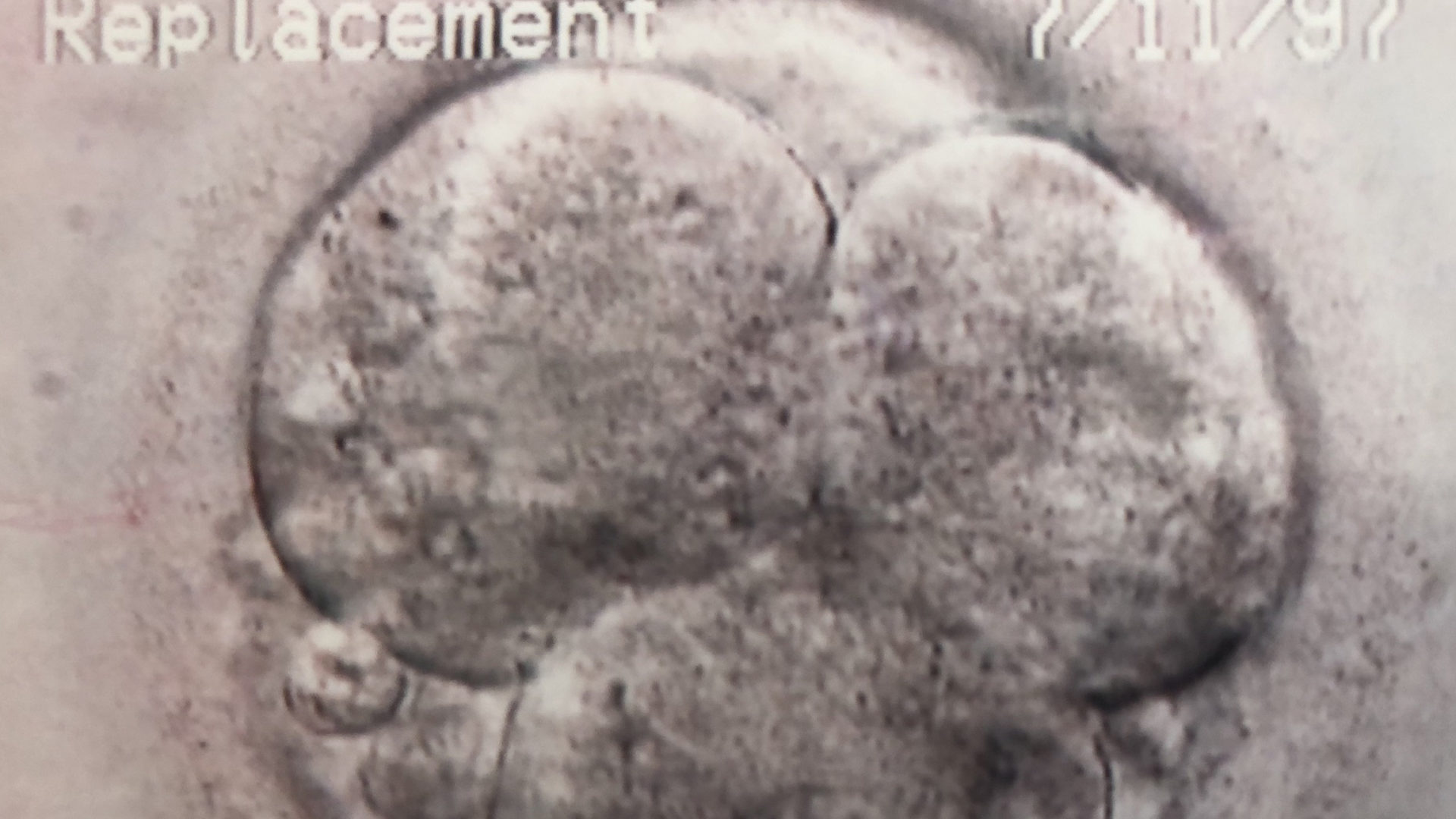

For the last couple of years, I’ve been reading everything I could get my hands on about the process of how the baby forms in utero during pregnancy— how the human body creates life. What sparked my interest was learning from my mother that I was conceived through in-vitro fertilization. I’m a petri dish baby. I am on this earth because my mom desperately wanted a daughter, and to get one— to have me— she was willing to take countless hormone shots and for months drove two hours before dawn each day to the hospital fertility clinic. She recounted the multiple failed pregnancies, some even lasting into the ninth month. After hearing this story, I could not stop imagining my parents looking down on a petri dish full of cells that would turn into their future child, me. It was inconceivable. It still is.

Throughout the interview, Imane’s children interrupted her by hanging on her leg, or by showing Laura and me drawings or some shiny beads on the ground. All the while, Imane showed each of her four children equal attention and what I interpreted as a sense of gratitude for being alive. I thanked Imane for sharing her story with me.

Despite getting stung by a bee, meeting Imane has opened my eyes to a different side of the birthing process and new possible work opportunities. I am interested in going into some aspect of the medical field, whether it be a nurse, physician’s assistant or medical doctor. Whatever direction I take, I want to exhibit the kind of passion Imane does in opening the eyes of other women interested in experiencing their child’s birth in a new, less-medicalized way.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.